it has been on his wall for a day or so, having appeared sometime at night, he thought; a wound, he would have called it, but more so from water-damage splitting through the wall into the sign of some exit or entrance than anything else, though he could not have said which or what. he had thought to invite others to see it, observe it with him, produce deductions, but then it was a damaged wall, nothing more. if, still, he hoped for more, it was maybe to the end that amidst causal assessment there may have emerged, “how does such a thing really appear?”, “is it a sign?”, “what does it mean?” but, then, it meant nothing; and that was of interest—did that nothing have something to do with the world? he couldn’t have said what, and he knew most would remain dumbfounded at what was not beyond description owing to how it had remained obscured, not flat and truly empty as it was; no, there simply was no description for it at all. he stared at it, its browning edges, the crowning hole, protruding inward, a mix really of exposed studs, wiring, rusty pipes, and drywall. “that isn’t it,” he thought. it was something else, he was convinced, in itself, and he still did not know what to do about it or how he could go about explaining to anyone what it was that had happened, what it was he needed dealing with, or what it was there was to see. he could have had it filled, and so he imagined thereby forgotten, but he knew better that his mind would see it through the wall where is eyes either dared not or would not, and he could see himself already wondering about it at night, just as he did now, staring at it without any conscience for it was. “what am I even wondering about?” he asked himself: what was there to wonder on? he thought, again, of some game he might have had in inviting others to speculate; he knew as well this would lead toward some mania of its own, when, dissatisfied, the answers piling in, each selfish in his possession of his own interpretation, who could have done anything to say who was right? and what would it have meant to have been right? it looked like a mouth, he thought, now beginning to count his guesses. where was the throat? he thought. and the spine? eyeless, the wound appeared like a perfect human being, he thought further, but for all the missing parts, not that that would have changed anything. “was a mouthless human not still human?” it did not appear to him, however, as something that had either happened or had happened, as it were, to something else. it was there, if one could say that, and this made it seem, again, if one could say this, as if it was not, in fact, there. in the frankness in which it was there, it demanded attention, of course; it was perfectly unusual to see. but, then, it was not as if one could say what one was attending to, or, say, which precise edge made it what it was or gave evidence as to what exactly had occurred. one suspected, if anything, that it had really been there, beneath the wall, and had only re-appeared—but was this likely? again, for all its frankness, this subdued it; it was so there that it defied the simple expectation one confided in description, for then so expectant was the description that all attempts simply failed. it being so special, so out of the ordinary, it defied any simple account of where it was meant to fit amidst the other parts, first, of his flat, then of anywhere else he felt inclined to compare it to. indeed, it became even vague, sunk into the wall, of which it could hardly have been part, either so exceptional it was, or so dumbfoundedly irrelevant, so that one did not really notice it after a certain point—again, it almost seemed to ask the question itself, of what here can be noticed? it was not then that it had appeared or had not appeared, but that it even this was too much of an assumption. it resolved one either to the distress of thinking that something had happened which had not, or, worse yet, that whatever had happened was not something of which one could take notice. even this, however, resolved nothing. was it an indifferent nothing that had happened or something still more obscure? he thought. and if nothing had happened, was it this that was the real nothing, either that nothing had happened and it was this not-having-happened which was nothing or was the nothing, not even the flick in the ointment of reality that had led one towards noticing something that was not there, but simply nothing—an unequivocal nothing, which could not ever be noticed no matter how hard one tried to? he suffered thinking about it, caught in the vicissitudes as much of his thinking as of the parched presence of the wound. ‘but, does not a wound imply too much?’ he thought. he could no more say, however, here was simply nothing; it was after all some nothing which was there, or, again, if not, then it was some true nothing, which made his mind blank upon each observation, defied him in his attendance of it. ‘did this not still occur?’ he thought. ‘like a trick of light, yes, it is really nothing, but then absence leaves something to be desired which cannot simply ever fill in.’ his blank mind, so it seemed to him, was the most interesting thing in the room besides the wound itself. it was the possibility of such blankness which astonished him, and to think that it was there, though, of course, it made no sense to say no, as if his mind was piecing together what it thought was nothing, so as to experience it, he presumed; and what experience did he gather? it was not that that blankness lent itself to thought, for it seemed to simply to be there, somehow with him, somehow not. it was some perfect blankness, which, again he could muddy thinking it was absence, or render it still more absent in thinking, such as he could, by imagining that it was not even there at all, that when he had seen it, the wound, it was there only ever in the corner of his eye; only in the lie of the perfect shadow of his blinded vision could he form an image of it, as if it were advancing nearer to him whenever he took his eyes away from him. where else could it be, he thought, but that wherever I am not, there it is, and wherever it is, I am not. he gave himself this corner-of-his-eye view of it, even as he never saw it, but then it succeeded that he saw it only when he could not see it, only when some kind of vanishing, which his mind could only just barely conceive, substituted for this vanishing the presence of something else which could never be directly looked at, not even as having vanished. it was never there, this nothing, he thought, but then, even now, I am not really thinking about it, and he knew, if only in his heart, how it was then that he saw it, if only with the corner of his eyes, this nothing, the wound, which had never been there to begin with. this did not explain the hole in his wall, which he came to regard contemptuously, feeling as he did that he seemed to discredit something which was ‘there’ only in proposing there was a simpler way in which it might be nothing. “it was nothing,” he explained to a few friends, who had come to visit him and observe it, “but it was more special in that one must imagine it really is nothing.” his friends looked at him incredulously, uncertain either of the difference or of what it was, then, which was to explain whatever it was that was in front of them. “it’s being there is not entirely the point. if it is there as nothing, then we cannot, in any case, observe it.” “so, what remains then?” “either it is nothing that remains or something we can only call not-only nothing.” “no,” interjected one of the friends, “it seems that if it is this blank thing, as you suggest, then we are not even looking at it, and it is this which is like a spot inside our minds. we place something there, which cannot be there.” “but, then how does the blankness enter into it at all?” he added. his friends looked at him confusedly, relenting only slightly to the mad premise. “it seems,” wagered another, “that what we have here is something that is not beyond description because it has exceeded it, but it never even arrived at it. but then this serves as a description. to say then that one has not really described it only muddies one further.” “one must imagine a perfectly blank spot in one’s mind,” he replied. “not even,” began one, final other, “not even, because this nothing is not here, then this is, well, nothing.” “but, that’s just the paradox,” he exclaimed now to all of them at once, “for there must be something there, stranger still than the simple fact that this here, following our observations, should remain nothing, and that is nothing short of the fact that it is, one could say less than nothing, though I would hazard the stranger phrase that it is nothing so truly rendered it defies description, not because it lacks it, but because it is impossible to describe.” “and you’re suggestion,” continued one of his friends, as if this were the natural conclusion of what he had said himself, “is that it is this which is before us? pray, then, how can we see it?” “but, you cannot see it!” he shouted, now rudely, so that his friends began to stir amongst themselves like some rattled heard. “what do you mean, we can’t see it? it is plain as day before us.” “no, no,” he continued to exclaim, “what you can see is nothing, sure, yes, triviality, great, but, no, the thing of which I am speaking of cannot be seen at all, not because it simply cannot be seen, but because it not able to be seen. there is simply, gentleman, quite literally nothing to see.” “then why speak of it all?” asked one of his friends exhaustedly. “because it would seem that this nothing which cannot ever be seen, lacking all depth, colour, anything, is not something of which we can even speak of as seeing or not seeing. even that fails. our mind conjures something up, which we confirm with the notion that it is whatever is absent from the world.” “I still cannot consent to whatever it is you say,” said one of them, he knew not which, so preoccupied had he become with staring at the wound, “because I do not understand why it has appeared at all then?” “it hasn’t,” he replied without looking at them, “there is quite literally nothing to see here.” he had invited a doctor, or rather a doctor had been invited over for him. it had been decided that he must have been suffering from some peculiar illness related to his fixation with the hole in his wall, or wound as he referred to it. “why is it wound?” asked the doctor, “seems like an odd choice of a word, suggests something got wounded.” “maybe, it did,” he replied shortly. the doctor sat beside him, having no other choice, for if he had attempted to place himself before who was now the patient, him, the patient, him, would have simply moved himself a foot closer to return to his unobscured vantage. “you say it is not really there.” “no, it cannot be there. it’s entirely the wrong word.” “but, then you’ve used the word wound. why? is it somehow there to your mind? is there something you can see, that we cannot?” “no, doctor,” he said blithely now, “I can see nothing neither more nor less than you. if it is a wound it is because, well, what else can you call it? it is not a wound like you or I might have, it is simply that, a wound. do you not imagine that something, when it is missing, should be called a wound of some kind?” “it is a wound of what then, young man?” “it is precisely its not being there which is the wound.” “so, what,” said the doctor, exasperated, “after all of this time are you staring at?” “you presume I stare because there is some sense to it. no, no. I am staring at nothing, that is entirely the point. there is nothing to be stared at, the more you point that out, the more I succeed at what I am doing.” “but, then it is there!” shouted the doctor. smiling, then, as if he had got the better of the older doctor, he said, at last, “you see, herr doctor, that’s the rub. it is precisely its not being so that makes it so.” in time, after much dispute and heavy wordiness, the patient now became confessor, or parishioner to the more reformation-minded, and the whole town which surrounded his flat had joined up in a great convocation, like one of old, to decide upon the fretting case of the young man gone mad staring at a hole in the wall. indeed, by way of some interjection, the case was eventually presented to the young man himself, so that he might, in contradicting it, make some acknowledgement of the matter of that of which he was meant to be mad. it had been agreed, after all, that unless the whole town was itself to accuse itself, of find itself accused of, being mad, it had to have the offending party, as he eventually became known, to acknowledge some sense in which he was, or as it might have happened, was also not, involved in such dispute as would warrant any kind of civilian extradition. even this he refused, however, in as petulant a way as he had done with all previous attempts to ensnare him to declare that the nothing was simply there, this having become the chief object of argument for, as it happened, both witness and defence, the offending party having no part in either side, as he had declared it an impossibility. his refusal to acknowledge of course rested upon the fact that there could be no acknowledgement, again, that the nothing was there, “for, my dear jurors, doctors, civilians, judges, lawyers, friends, family, and all others present,” indeed this last affection became the only credible part of his speech to which he himself made what was considered sensical reference, “all others present,” it being deemed at the very least a fair admission of sanity; though this was, it was argued, hardly what they were trying to prove. indeed, his refusal to acknowledge rested equally upon the affectation that, whenever they should ask him if it was really there, the nothing, he would respond, “I say to you and all others present,” the various front and back benches tended to lean in at this point, “it is precisely its not being so which makes it so.” this last part could, of course, have become as obdurate, and obdurately-viewed, an affectation as the others, but seeing as it was this principal argumentation, though it was refused to be called that, and therefore to be even entered into evidence, which had stumped all those around him. eventually, however, the priest was made to enter, it being duly conceived that only the graver suspicions, and therefore the graver methods, could now be conceived as explanation for whatever it was that was “afoot”. it was this which became, it must be said, among, admittedly, many others, the affectation of “those present” to the end that the business, it had to be said, could simply not be described in any simple parlance and so had to be referred to as that which was simply “afoot”, underscored, on occasion, by the more detail-minded, as “the business afoot concerning the nothing that is there”, with some occasionally opting for the laconic rendering of “the nothing that is not there,” this being, in point of fact, technically the central objection of those on the side of the defence, the town having been split between these two nothings, one which was not there and one which was. when this was presented to the offending party, he nodded his head, as if in agreement, and therefore seemingly joining in the general consensus that he was, after all, surely, speaking of a nothing that was not there, but, then, just as he was meant, so they thought, to give his hearty consent to this formulation, he replied with the old affectation, “ it is precisely its not being so that makes it so.” the priest, learned in theology, took this as his starting point. “so, then, son, the negation would imply that it is the first nothing, the nothing that is there, which is, it must be said, the view of the greater half of the town, which is that there is a certain nothing you are staring at, but that it is no more than nothing.” “I cannot consent to say that it is no more than nothing, only that it is certainly not there.” “but, you are on record saying it is its being the negation which makes it so. what can the negation here be but that it is the nothing which is there?” “I mean to say that the negation of it being the nothing which is not there is that it is not there, which is precisely that it not being so is what makes it so.” “because you mean to say it is neither.” “the negation of what is not so is not what is so, not when what is not so is not simply not what is so. there is neither the nothing that is there, nor the nothing that is not there. in one sense, they are exactly the same thing, nothing. which is why it is only when one has the negation that one can get to the point that it is its not being so that makes it so.” the priest did not understand this last formulation in the slightest and so opted for a more human approach, “can you tell me, why, then, you look at it?” “look at what? I’m not looking at anything.” the priest sensed a slip-up here. “if you aren’t looking at anything, are you not looking at the something you are not looking at.” he smiled at the priest, and said, “can you, of all people, not imagine such a thing as a perfect nothing, something so blank it cannot even be contradicted. do you think that you could say you see it or not?” “I would think that if such thing existed you would be carrying it with you all around whereever you went. you would not be able to say when it was not with you.” “and, yet, if you ever said it was, it would be nothing. the question, of course, then, is of this nothing which is really nothing. that’s the question.” “my son,” said the priest, “it is not a question.” with that the priest too left. it was not until a great deal of time had passed that an unassuming person in the town was passing, having driven in totally unaware of the circumstances that had befallen it, the entire place being, after all, in disarray and suspension, all business having come to a halt, as all that remained were those who remained within the disputing halls debating, and who largely hung upon a faded transcript of this last conversation between the offending party, though he was now generally himself referred to rather ambiguously, and conflatingly, as the wound, and the priest. this stranger, though unprovoked, took it upon himself to speak to everyone so as to gain a measure of what had happened, inclined towards the notion he might be able to help, and it was he went into the flat, having spoken already to every other occupant at that point, meeting there where what must have been the singularly sane person to whom the obvious design of this spectacle must be owed. he was not disappointed, but found in the man the perfect expert of whatever dialectical sore had erupted into the scene, the man having even had occasion to drill, so he imagined, into the wall a perfect representation of what was to be the hopeless wound. following some hours with the man in which he heard each line of dispute, he asked him, at last, how he had come by this knowledge, and why he, out of all of them, seemed to know it so perfectly. he did not inquire, it must be noted, as to the question of the wound itself, satisfied as he was with the pure demonstration, after all, that it was not, in any case, to be found. the man to whom he spoke eventually replied to his question, saying, “I could not tell you who first mentioned the wound to me, for it is not the kind of thing that can be mentioned. I certainly cannot tell you who first saw it, for it is not the kind of thing to be seen. but, then, as I have often said, it’s not being there is precisely what makes it so. those who say, what is there is not there, but this is but a philosopher’s trick. it makes no difference how you are content to formulate what you cannot formulate.” “yes, I wondered this myself,” said the stranger, “and it seems to me that the townspeople have, so I imagine by your design, missed a crucial discursive move here. they were inclined to say that, then, there must be some formulation which is adequate, but there isn’t, is there? if I am correct in understanding what has gone on, the wound does indeed exist. one could even say it exists more than anything else, and that everything else is rather a fiction of its formulation. but, here, one must go a step further. if we were to imagine the wound in the world as like this hole here in the wall,” and he pointed to the wound rather scholastically, “then we might ask of it, is it an entrance or an exit, thinking it must be one or the other. is it not, however, that what all others have missed is that, it is in its impossibility, which makes it there. what is, finally, there, is not, as all others had thought, nothing, but what was impossible. nothing, for any interlocutor, was a category, like any other, to be overcome. what was there, finally, was what was impossible. and once one admits to that, that that impossibility is there, one accomplishes that very disorientation which is the problem of the wound itself. one must not, after all, ask, what is that thing we call the wound which is there in the world, but what is the world which is there in the wound?” and when the stranger had finished speaking and his eyes flushed with a sense of strange epiphany, he turned towards the man with whom he had been speaking to find he was no longer listening.

what is it I am able to do? I mean, there must be something I can do—or do I presume too much already? am I ever able or unable? what would either consist in? and that either, what is it? what is our politics? and where do we press it? is there a specific subjective disorder which motivates us over others? surely not. for that would presume the very thing we are missing. call it standing or position or reputation, there is something, like good nourishment, we lack, which leaves us starved—of what? we would like to say we understand it, but then we know as well that our problem is not that we don’t either understand or know what we want, but that when we say it out loud no one seems to understand. to an extent, this resolves us: we imagine that if the question alone confounds then we must be on the right track, if only we were not interested, in the end, in being understood. what, then, are we to do? should we accept that then our task is not one of persuasion, for that would presume there was something to being understood we considered, on first principles, to be either productive or desirable. indeed, this not being understood seems to us productive in another way insofar as it may testify to some letter we are pushing, which now forces our adversaries to accuse us of obscurity or worse of a vague indeliberate dreaming. what is clear, however, is that while we have our conditions on the one hand, those circumstances (“not of his choosing”), which make a man and ourselves in our resolve, on the other, lacking all objective account and understanding, but in any case seeking subjective demonstration. our not being understood for our question therefore allows for something understanding, and even acceptance, of our answer. as we have realised, there is a more agreeable compromise to many to accept, if not our terms, then the exception that is the answer—so long as we never ask again. if we could be understood, however, we could lose that very resolve which allows us to act as we do: we doubt ourselves, and in doubting, submit, if not clarity to ourselves, than forthright commitment. even still, we have learned to become interested in this subjective demonstration of ours over and above any objective persuasion. largely because all that that objective knowledge, we are convinced, will ever consist in is the demand, based upon a more general assessment of its conditions, of that subjective demonstration. this, of course, is paradox: we would not really seek to be understood subjectively, but merely to put aside the notion of either simple persuasion or indeed of some possible account of the facts, which sufficiently complete would supposedly render immediate agreement. this fantasy we are happy to forego, not least because our demonstration is not of the facts, but being, we believe, necessarily subjective, therefore concerns what cannot ever be, in any case, explained—objectively. to our mind, we return to our two eventualities: the conditions, arbitrary, and the pure resolve of someone, who neither understands himself, nor can claim the honour or shame of not and so must stand his ground, legitimately or illegitimately—he knows neither. his capacity is one, ultimately, of subjective wariness. now, however, this is itself but a demonstration of what cannot be overcome with any appeal to what is “really going on”—one must instead insist upon the intersection of what is missing with what is not; they collaborate: the question, when it is understood, is no more understood with what is imagined to be understandable itself; rather the true paradox of the subject is that nothing is missing from his explanation, except that that impossible examines itself, which finally renders it a fact. in short, when you do understand, you can’t explain it. this poses a problem for politics, which reinvites our split: consent, then, to manipulate the conditions as if therein lies the hidden letter of your persuasion or force a confoundment of every person until they hold their ground before what they do not understand. how to escape this antimony of persuasion and fanaticism? perhaps, again, by asserting that what is not understood is not a testament to something missing, but that there is a pure missing; an absence, which is rather just silence. you cannot understand—before you do. even then, avoid the eucharistic trap: there is no revelation to come. you will never just understand; that recognition which appears is retroactive: when it happens, everything is already different. how do we measure the difference? some say the subject is the difference. it would seem, however, that the position is far stranger. the change that occurs is not a change (in substance), but an understanding appears, itself a synthetic product of our recognition, and there is then only radical acceptance left. does this mean, in the end, we do present a sequence of synthetic facts? no, because one traverses even this synthesis to the point that this very synthesis itself is one of the facts to be accepted. you accept the antinomy; but, as what? not as a simple stutter or disruption; you accept it as the dialectical point itself of traversion: you install, not persuasion, but critique; and this satisfies your subjective demonstration. you are invited to break down whatever proposes itself into the antinomy of its recognition.—and then, you propose to accept something; it is the revolutionary scansion itself: you cannot convince people, because there is nothing of which to convince them. how do you accept the world as it is? try to do something and see what happens. then you accept. like a doctor diagnosing through treatment: there is human society, and our project. “what is really there?”: be prepared to see antinomies themselves, and then when the treatment fails, you try again. what is the revolutionary doctor but one who revolts over nothing, and in doing so finds the diagnosis for a different illness. there is no sense, dialectically, to diagnose, then treat; but, only, to treat, even when, if not most especially, nothing appears wrong, and then find the diagnosis. if we revolt over nothing because the diagnosis does not ultimately interest us, only the treatment.

it would seem that a culture of polemical letters is agreed to be beyond us. we need not try to contradict each other in writing, our despair at the thoughts’ of others having dissipated, or we have simply become comfortable with, and so have in a sense relented to, our various inner seethings. whatever the case, we are anticipated by a more serious issue related to human polemics, one seemingly independent of whether we should engage with them or not. to some extent, the problem is where, or perhaps more ambiguously, to whom, we are meant to send these letters. we ask ourselves with what ink or on what paper, convinced that the question of under which candle’s light or within which dingy attic we should write is soon to follow next. must we all become raskolnikov to believe in the writing of ironic letters? to those familiar with their history, the answer would be a resounding no. the russian version, after all, can hardly be called a simple intellectual culture of exchange on the issues of the day. still, does our sense of loss, or having lost, find its origin in a lack of culture? lacking institutions, we come to lack both issues about which to discuss and the language in which to discuss them. the topic of ironic letters would also seem to contradict the more sincere formations of our generation, though irony is hardly the opposite of sincerity, but its most astonishing companion. it lends acidity to sincere points, which may, without its influence, appear far more insincere, lacking the depth and self-distance necessary to promote any kind of serious understanding, either of oneself or the world. it would seem, however, that all of these explanations fall short. we are left with the question of the candlelight and the attic, for what else can explain our poor intellectual habitation than that, at base, we somehow lack materials? a dialectical suggestion presents itself: what we have too much of is an expectation of a certain material hardiness, one which only actually succeeds at ever, and therefore merely, ideologically supplementing our effort. it is this effort, which is forced to degenerate into what we may only call the unresolved enjoyment of our own participation in the matter at hand. how to understand this? we publish, and, in doing so, we make our lives harder. this is not the 19th-century, and lacking as we do a real press culture, we can only produce frankly simulacra or otherwise pastiche versions of what came before—but without substance. indeed, in supplementing this substanceless ‘substance’, lacking as it also does any real content because it lacks any serious determination of what is around it, but merely operates in the bubble of boutique publishing, this ‘material hardiness’ shows its hand, of course: the ‘substance’ here is the operative achievement; we are not interested in publishing anything, but in publishing itself. we make it harder on ourselves because of an acknowledged enjoyment to this difficulty which serves to supplement the fact that, if we took the easy route, we would be faced with the more vicious and immediate crisis that we don't actually know what to write. the ‘easy route’ is then ironically actually the more defiant one. what defines this easy route? it is the digital. perhaps, not a very interesting or surprising answer, but more robust than you might imagine. after all, what we allow with respect to the present toxification of social media is nothing but a barely-restrained resentment which reveals itself in the fact that we let that spectacle take place as if there was no other option. we also conveniently ignore the ugliness of humans, and their thoughts, which surely should serve as the soil to the stalk of all serious opinion-making. in other words, we are content to let it self-destruct because it forces the derailment of the easy route and therefore the underlying crucible of having to face our own thoughts, or lack thereof. indeed, an interesting ideological irony appears here: the detritus of human expression that appears on social media is, in a curious way, preferred to the horror vaccui of our present deadlock with our own inner lives, to say nothing of the outer disintegration which naturally seems to follow it. furthermore, perhaps one should read the explosion of monstrous thoughts on social media as strangely anticipatory of, or otherwise parapractic with respect to, this void, above and over which these thoughts appear as hysterical expressions; desperate, overblown messages of the guilty to signal the guilt they feel at really being, or thinking, nothing. this lends them some temporary, or vanishing, truth, which is perhaps why they are ultimately so politically subversive, and not, at times, without insight. this enjoyment, as an unacknowledged phenomenon, concerns the suturing of our excessive, hard effort. it helps us get through it. at the same time, it is not acknowledged and this means it lacks the very signal-quality which defines serious enjoyment: its relationship to the impossible. one enjoys, after all, in view of, and therefore not against, the impossible. it is enjoyment which is the difficult, and even paradoxically impossible, thing to remove. to ignore it is then to add some ‘surplus’ enjoyment typical of what is ultimately yet another repressed phenomenon of what I must regretfully call the dynamics of capital. before you dismiss me as a marxist, which I nevertheless am, consider this in the vein of a good, old-fashioned, leninist critique of the left itself, i.e. all of the leftist, posing, boutique publishers who rely, if anything, upon pastiches views of marx to match their pastiche view of the radical presses they shamelessly try to emulate: this enjoyment goes ‘surplus’ because, in being unacknowledged, it must go unconscious; it must submit itself to be surveilled elsewhere. this elsewhere-surveillance is precisely, however, what allows it to suture in such a compelling way, if only you don’t try to lift up the mask of its effort, or, in this case, turn over the cover: it is entirely ‘capitalist’ after all to promote a radical surveillance of what is meant to exist as unsurveilled; a ‘social phenomenon’ which has value, but no social meaning. this is one of the serious paradoxes marx did unveil. indeed, this awkward surveillance of ‘nothing’ conceals the horror of this intrusion of nothing in the first place; the horrifying nothing of the act of surveillance itself, which sutures ‘value’ through a reference to some suturing elsewhere. in short, a phenomenon can ‘exist’ so long as it is at least acknowledged ‘elsewhere’ by capital, which one should read as the unironic reference point, nevertheless hidden, which makes so much substanceless substance possible. consider, for instance, what literally, materially underpins the ‘hard way’ if not the funding-dump that defines the middle-class dreamers which typify this class of boutique publishers, though it also includes certain elite circles who generally hire this unskilled class of ‘workers’. but this in its own way misses the point. one must recognise, after all, how it is the obscuration of the impossible, typical of this repressed enjoyment, so that one enjoys in secret, forcing explosive symptomatic contradictions in time, which makes, once again, the one thing that is so crucial about enjoyment, its wagnerian core, if you will, disappear: one can face the impossible over and over again, if only one can still conceive to both enjoy and confront the enjoyment which emerges. those who pretend not to enjoy are repaid in surplus enjoyment, and this only really serves to obscure their relationship to the impossible, foreclosing any actually possible radicalisation. the ‘easy road’ by contrast is to confront the impossible and therefore to risk enjoying. perhaps this enjoyment is no less dangerous because one can properly go mad. there is no naive limit, but the interior excess really of the enjoyment to be found in ‘throwing the javelin into the void’ as beckett puts it. even still, the point is to be found in, actually, the underlying political economy which emerges with respect to the materially easier path—if only one can handle the impossible that comes with it. this impossible is, of course, ‘not knowing what to say, think, or write’. the political economy that should naively appear along with this uncertainty is of course precisely what emerges, if not to synthesise exactly our effort, for that is the very subject of marx’s kritik, then to underwrite a certain enjoyment, but also, strangely enough, political effort which we may exercise in en- and adjoining ourselves to what is impossible. it is therefore the digital which serves us as the polemical instrument par excellence precisely because it is the scene of our society’s letters. one should embrace the vengeful efficiency here of the digital, not as a business concept, but as something which engages us with the more immediate stakes of our political society as something within which we exist and about which we discuss. recall how the monsters of social media remained outlawed so that we will not detect the basic political subjectivity which underpins their, admittedly sometimes maddening, expressions. it is not, then, that our suggestion is to pair this rabble, or lumpenproletariat, if you will, with some bourgeoisie of digital publishers, more elegant in their expressions. on the contrary, one is far more interested in the leninist notion of the professional radical: someone who writes from within the basic political stance of this relationship to whatever it is we are not facing about our society, draws it out precisely, and ultimately follows it through to its end. in so many ways, this is the proper social task of society itself. we do not merely ‘produce’ and then understand our production to merely have left out certain subsections of society; we understand by the term production itself some material repression of our social concerns and relations as a society. we are not ever actually just producing. everything exists in some radical social context which expresses and underpins nothing short of its desire, enjoyment, and fundamental impossibility. the church, as it has existed, was not some entity of surplus authoritarian rule, which is only how it became portrayed in the post-reformation, enlightenment critiques, which had already gone some way to formalising the very term ‘production’, but rather a deeply integral ‘unit’ of social expression, without which society would have been blind as to its fundamental human, or, in this case, higher order commitments. one can, nevertheless, try and reduce the state to some realpolitik, material agent of social cohesion or stability, but this merely reacquaints one with ivan’s stunningly bitter story, the grand inquisitor, in which christ’s second coming has become unnecessary because he has done all that he was needed for and the church’s responsibility is to feed the masses, not to move them. the irony of ivan’s tale is, of course, contained in the fact that the inquisition priest who relates this cruel insight to Christ does so nevertheless in full acceptance of Christ's existence. one should impute a similar irony to contemporary critics of the church: you really believe, but you are either mad at God for disappointing you, a view you have likely gained in having supposed him to have been unfair in some naively liberal way as opposed to beginning with some dictum, like that of arvo part’s, “have you thanked God for this failure yet?”, or have similarly reduced His role to that of naive material benefactor. in any case, this is but a taste of the serious social task of the desire, enjoyment, and impossibility of civil society to which such professional radicals supplement as much as any ‘producer’ the means by which to affect, further, and membrate society’s existence. by means of a further detour into our ideologically polemical society, consider recent events in our fair city of montréal. anti-nato protests collaborated with pro-palestinian protests, driven likely by aimless professional anarchists, the kind of professional radical very much to be avoided, into some kind of civil disorder, resulting in a slew of conservative reactions to the effect of ‘montréal is burning’. to this, rather curiously, leftists online responded by seemingly wittily refusing this implication by describing themselves as going along with the usual business of their day, as if to say, ‘how can the city be burning when I’m just going to cinema?’ to this, of course, more self-conscious leftists responded with fury, likely out of shame, guilty, and embarrassment, that these leftists were stupid enough to have thought this an appropriate response when all it actually does is subvert the now seemingly intended civil disorder of which apparently leftists are meant to be proud. I don’t know who is worse. one should begin by insisting how there is, indeed, a liberal bias to be found in these less-committed leftists, but that it merely implicates the more radical leftists in the fact that their achievement is only readable within the very liberal horizon of law and order, of civil order or disorder. far from this liberal bias subverting the ardent, radical leftists, it reveals in what respect their so-called politics entirely lacks any actual program on the basis of which one might really say they are either radical or leftist. anti-capitalism is the terminological equivalent of bland dog food. it means nothing. anti-nato seems similarly misled. the only hysterical accomplishment, then, of this left was to produce an awkward rift within its own fierce members to the effect of exposing the showmanship of their leftist commitments. one should, after all, go to the end in the critique of even the radical left’s liberalism. their programmatic approach to representation, for instance, is the political equivalent of boutique publishing. they deny enjoying what they are doing, claiming they are taking the hard path, despite the effectively easier path of writing down one’s committed demands and following them through. to those who retort by saying, ‘but the institutions won’t allow it!’, ask yourself how it is possible that the left has become only definitively leftist insofar as it is really anti-right, or in some cases, anti-trump. this is liberalism by definition; it trades upon merely representational exchanges as opposed to questioning the entire paradigm of a given institution’s answer. to those who then suspect an inconsistency given my dismissal of anti-capitalist, anti-nato commitments, note that my point is their lack of specificity, betraying as I feel this does a serious lack of understanding of that which is demanded, implicating such ‘leftist’ programs yet again in the fact that they seem to have chosen the hard path of anarchist resistance and civil disorder because they wish to avoid the monstrosity of either not knowing what it is they think or what their plan is. is this not ultimately underscored by the vanity of believing that forms of solidarity and, indeed, actual civil disruption are reserved to, yet again, some 19th-century crowd pastiche, as if that was not itself a phenomenal example of an hysteria typical of the time, not to mention one contractually enforced, if one can put it that way, by the undiminished presence of the urban/agrarian divide which had come to specially designate industrial labour workers as really a class of un-landed farmers who had now been forced to sell their labour time, matched in its absurdity only by the image of some stinking cow-herd coming to fill the streets after being sent away from the dairy farms. it was not, in other words, an accidental assembly of people, let alone some liberal assertiveness in practice; it was entirely owing to the ‘necessary contingencies’ of the conditions of the time that people assembled in the way they did. one should no more however dismiss today’s leftists for assembling without direction or conscious purpose, but nevertheless criticise, if anything, the vanity of purpose which presents itself as if appearing were the only achievement of a march. such reductions to appearance accomplish what the false neutrality of surveillance does for capital: it obscures the proper impossible which makes enjoyment (and politics) possible. after all, once you feel the purpose for what you are doing is declarable in advance, why meet up? this, of course, torpedoes such marches with a curious sense of guilt: is there not something else we could be doing? this furthermore embitters the undecided against them, who feel they really ‘mean what they say’, i.e. that there is no deeper message or movement to what they do. those who try to supplement this with greater and greater condemnations of western institutions only really seem to obscure the need for serious political stakes: rather than deepening the commitment, it only makes the message more reified and pre-chewed. this guilt emerges with an awareness of the naive efficiency of the easy path, so that, in the end, however, this guilt should actually be seen, if anything, as preferable to the suffering endemic to a relationship to the impossible. a polemical culture does not appear anymore then by accident, except for the accident of the impossible. if we are to have one, we must take the easy path. indeed, let us consider two other peculiar examples of the easy path. john adams, the american founding father, revolutionary, lawyer, statesman, and diplomat, only came to join the continental congress after having seen the effect that mob mentality would have upon what was to him the possibility of a serious political movement. far from him joining in the civil disorder, he actively tried to dissuade them from the hysteria. in doing so, he radicalised the movement. in such situations, it is moderation which serves to much more effectively gauge the stakes, precisely because the withdrawal one exercises in moderation acquaints one with the enjoyment that is often at stake. one cannot not enjoy, which is precisely why one invites the suggestion of it so as to expose the inconsistency of one’s actions. often people stop here, however. one must go further in suggesting that it is only this inconsistency which can then properly face one with what is impossible, with what one is not facing (as opposed to, say, what one is simply avoiding). in dissuading the mob, he forces them to confront the enjoyment that is latent in their politics. in doing so, he exposes the inconsistency of their political movement. he, himself, enjoys only to the extent that he does so warily, aware that the unavoidability of enjoyment taints any serious politics, but also therefore implicates it in whatever it is that is impossible. for instance, when one takes upon oneself a task that one does not know how to do, or for which there is no guideline, the only way, after a certain point, is to structure this engagement through enjoyment, through regimes of discipline or aesthetic, etc., which allow one to cross the boundary of what is not there over to whatever is on the other side. one must have the counterbalancing impossible so as to, in a sense, vindicate what are otherwise empty political or ethical acts of enjoyment. to do so, however, one must, again, face the enjoyment that is there and, again, vindicate this enjoyment with the impossible, with the invitation of the impossible that is there, the underside of enjoyment. the result is a certain wariness, in that one observes the inconsistency of the hysterical effort, but cannot turn one’s eyes away, aware that there is no simple, other option on the basis of which the hysteric might return to his or her place (in the impossible). the only option is then to get one’s hands dirty with moderation. the second example of the easy path is more dialectical; it is that of malcolm x and martin luther king jr. it is often argued now that king was preferred over malcolm x in that, together, they had put civil society into agreeing to choose the supposed lesser of two evils. one must reject this, in at least two ways. firstly, it is really king who is, in his moderation, more radical, precisely because he does not legitimise the hysteria as if it were a ‘consistent’ demand, whereas, of course, what makes it both legitimate and political is that it is inconsistent, and it is entirely arguable that one must risk inverting the order here: it was malcolm x who was ‘supported’ by established powers precisely because he would put at risk the effective legitimacy of the civil rights movement. do not underestimate in what respect malcolm x is fetishised ‘as if’ he would have proven decisive to extending the civil rights as far as it would go. the illegitimacy of trying to promote ‘legitimate’, however extreme, demands is countered only by the legitimacy of illegitimate demands, such as king’s speeches in the north and private correspondence, where he advocated anti-capitalism and viewed his struggle as foremost a class struggle. this ‘insight’ is not really proposed as a demand, ultimately, but really as something that cannot even be naively conceived, which once again demands a wariness with respect to what is asked. this provides the final twist which is that, rather than it having been a choice between king and malcolm x, it was a choice between two different versions of king: the one who could be confined to a demand that was not hysterical and the demand that was, in this case, underpinned by a more radical class hysteria and would, and, indeed, did, invite the wary moderateness which made martin luther king jr, in fact, such a professional radical. what is finally necessary to say, or repeat, is that any such culture of radical or otherwise polemical letters must be done, at least to begin with, digitally, because it is our easy path. we make our lives harder in the best sense by trying to publish in these bespoke aways, indulging anarchist politics, etc. we must, instead, opt to make our lives easier in the worse way.

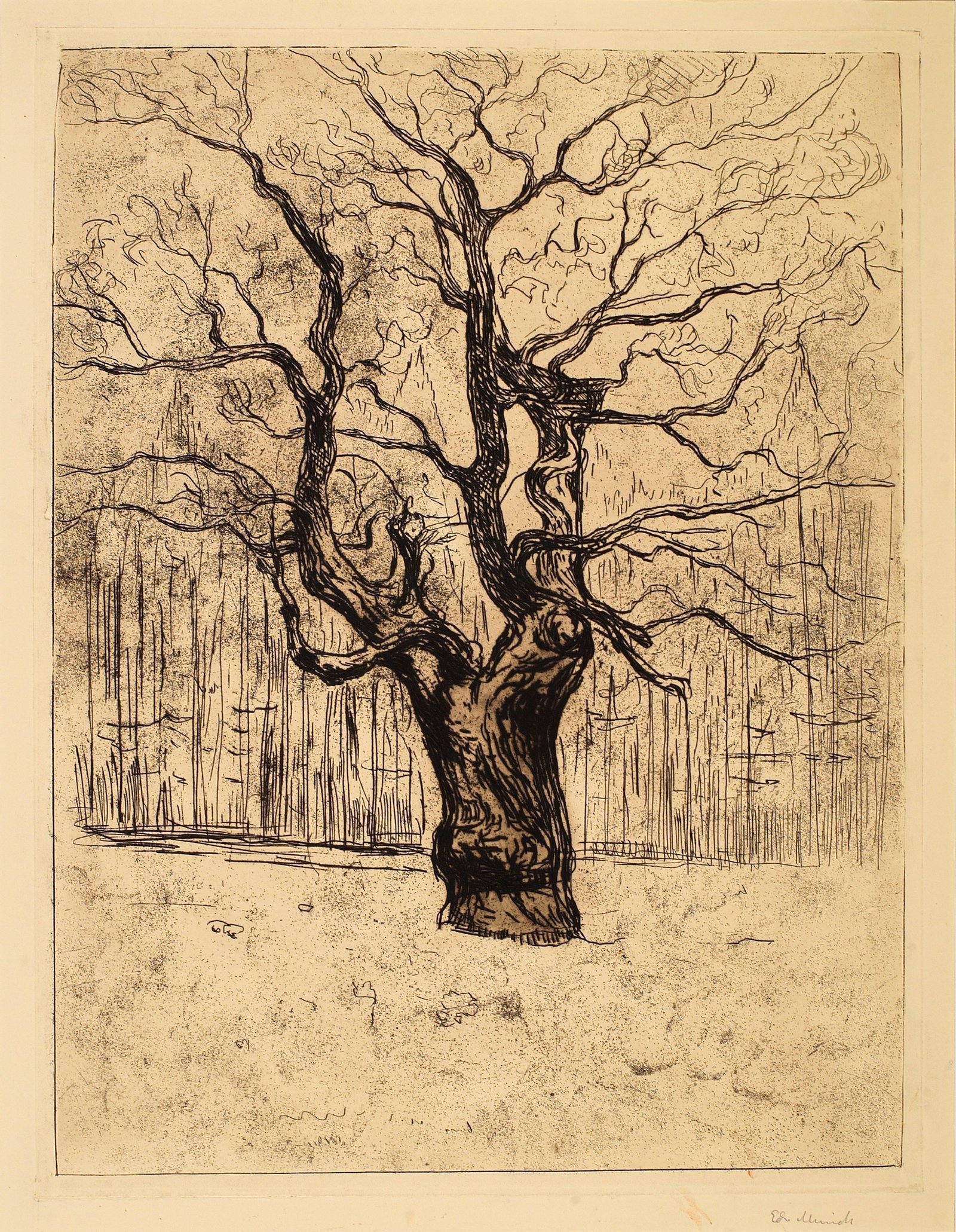

the trees outside stood still, and he observed them uncertainly from within his flat. he had an appointment which he was meant to attend, but it was simply raining too much outside, he reasoned, that he could not possibly go out. if he went out, would it not endanger the very thing he was seeking to protect in going out for an appointment in the first place. what was the appointment, anyway, he thought further, having forgotten which of his many visitations to which of his many doctors he was meant to pay that day. as he did this, which is to say, reasoned, he sat in his small, but comfortable chair, fidgeting his hands, buried as he was, owing to his peculiarly small frame, within many blankets he had layered on the chair to either keep him warm or keep the cold away, he never knew which, for he never knew which he was, and he looked out the window, observing it as if in study of it, uncertain however what he was ever meant to be looking for, whether it had not already happened or was just about to. it sometimes occurred to him that he was not looking outside the window, or was not meant to be, but was looking, or was meant to be looking, directly at it, as if it was the principal object of focus, and this sometimes led him to the exciting, but equally paralysing thought, that since we had in our short lives had occasion to observe others looking out windows, we had always concluded the thing they were looking at, for, or upon must be outside it, beyond it, when indeed, it seemed just as possible that the thin frame of foggy, yet clear nothing was of similar attraction, if for no other reason than it was, however impossibly, what people at the end of the day had been really looking at all this time. he was, perhaps, in his early thirties, and if he had forgotten the number it was only because he spent so many of his days inside, cloistered away, unoccupied utterly with any business, that while he had counted the days since his birth with an astonishing exactness, it was possible that one day had melded into the next, or indeed that a whole year or so had passed, when, in a similar attitude as to today, as all other days, he was only ever to be found in his living room, looking out the window, reasoning. it was not then for him to say which age he was, and no one having appeared in his life for a very long time meant it didn’t seem to be anyone else’s task either. his doctors had tried to come to some agreement of the number, but whether through his having misled one, who, then, in consultation with another, either similarly, or correctly, but self-doubtingly, misled him, there was no consensus among them. the result was that he had had to schedule appointments in order to rectify endlessly mismatched consultations, figures which had no place in any objective medical history, entire episodes of his admittedly daunting, but rich, medical life which were either central to prevailing theories of his doctor’s of his condition, or, indeed, as it was yet to be determined, conditions in the plural, or had never been mentioned to or heard of by one of his doctor’s, which had then been either brought up as if they had been historical benchmarks or else had been forgotten entirely, even by him who was meant to be the possessor of the only reliant memory of such things upon which everyone, likely very mistakenly, but unavoidably, was relying. this left him in such a confusion that his own answers began to contradict themselves, not on the basis of any intuition of knowing better, nor indeed any inkling of what may have really happened, but simply out of the shear reflexivity of his own encounters with the details, as if he were a perfect stranger to them. this led him to then invent, or supply factually, things which appeared to him to be sensible or possibly accurate, owing as he felt he did, though this was in some way, shape or form, likely related to whatever was at bottom wrong with him, some responsibility to uncovering what the general picture in the end was meant to be, or indeed what particular things he was meant to be suffering from, had suffered from, or worse yet, as it was always part of any serious pathological diagnosis, would suffer from, thereby encompassing the whole of possible human illness. he fully had the expectation now that he had, in any case, missed whatever appointment he was meant to attend. of course, it was very likely he already had another one, at this exact moment, and it was just as possible, if not downright likely, that it may have in actual fact been this appointment he had remembered he was to attend today, having only misrecalled the time, while the previous one was, in fact, the one had actually forgotten, though was, nevertheless, prepare to attend. in fact, it was possible that the entire day was full of appointments and he only had to step outside and go to one of them at any hour, or indeed at any of his clinics, and he would find someone waiting for him, though it was just as possible that the entire was wrong, that this was one of the days in which he had no appointments at all and was now sitting here worrying himself needlessly. he was sure though he had the right one, and if it would only stop raining he might be able to reach the doctor and, even if he had had no appointment, mention to him having either forgotten it, if it turned out he had arrived to it too late, or, again, there being no actual appointment in point of fact, mentioning this latest bout of worry and mismanagement to the doctor as perhaps formatively pathological. unless, of course, he arrived at exactly when it was to start and then how would he mention to the doctor that he had worried with great anxiety about whether he was going to late, the appointment was scheduled, or, indeed, whether it even existed, when he had arrived entirely on time and to the right appointment. was he meant to sit there fidgeting then with that stunning knowledge of nothing, fighting the impulse to reveal to the doctor, who would scratch his scruffy beard and make surely a dozen observations just from the state of him alone, that he was really was quite sure he was going to be late or was going to arrive to an empty clinic, even as he was sitting there, perfectly in place at exactly the right time? would he then hesitate to mention even this, fearing it was somehow too absurd to mention how he had had a problem with arriving at exactly where he was supposed to arrive at, or would he then not find himself even more anxiously engaged at the thought that he ought to be mentioning this, and now wasn’t, making what was perhaps a curiosity of human folly into a detail, not only utterly indicting, but perhaps pivotal to his doctor’s evaluation of whichever critical stage of his formative pathology he found himself at? of course, this would have continued until he had mentioned that he already thought all of this through, but then he would also have to mention his having thought it all through here, and that he had never actually attended the meeting because he was too busy thinking about whether it was supposed to happen, or whether he had simply remembered wrong, which may have constituted an actual problem, if only for the fact that he would missed the appointment surely then and would have to go about the bother of rescheduling it then, knowing that, to even do so, and in so doing, find out the quality of his particular despair, he would have to scour his brain, yet again, in search of which appointment it may or may not have been and which doctor he was meant to have been relating the fact of how he had missed his appointment because he knew it was either going to happen or not. as it was still raining, however, it was in all actuality really owing to this that he found himself now perilously unable to move, even as it was possible that it was not raining, in fact, at all. this he doubted, not owing to the possibility he was hallucinating, which he had already considered, concluding that then this entire thing could have been a hallucination, not to mention this very train of thought, and resolving then that he might as well continue as if, even if it was a hallucination, it was a very problematic hallucination; one that did not seem up to scratch what a hallucination might be. indeed, his doubt regarding the rain hinged on whether or not the droplets he saw were not at any given point the last droplets of rain that were to fall, meaning that they it was in fact not raining, but had only just rained, while any other proceeding raindrops would have to be concluded as the beginning of a different rain, which while possibly contiguous to the previous rainfall, could not be confidently concluded as being so. he stood in this attitude of considering how it was all at once raining, not raining, about to rain, having just finished raining, and even had not ever rained, for it was either not part of the hallucination that it really was raining or it was a hallucination already, which, to establish, relied much more on the former point than on the self-evidence of the latter. of course, this led one down the possibility that at any given time there was some hallucinatory effect which one could doubt either as a hallucinatory effect itself or as a hallucination, never knowing the difference. though he had reasoned all of this according to the fact, however, that it was bad in some way or another that it was raining, and that therefore he could not attend his appointment, whereas it was perfectly possible the opposite was true, that the rain posed no impeident whatsoever to his condition. it was therefore impossible to say on the basis of whether it was or was not raining whether he should or should not go out, even as establishing whether it posed an impediment was as difficult as saying whether it was raining or not. this went so far in his mind that it led him to doubt whether he was in fact ill at all, and whether or not, in actual fact, however, this was not itself part of the illness, that he would not think himself ill, or that thinking himself not ill when he was in fact ill was not the exact illness itself, so much as it was uncertainty itself of saying which was which. was he ill because he doubted if he was or did he doubt because he was ill? it was possible then he had no appointments at all, and he mulled the terrifying possibility over that he had imagined all of his doctors and appointments in his own head. he also considered how it was possible that he had really gone to every doctor but had not really been ill, which, if it was an illness, was of such a kind that it seemed to be beyond the realm of any simple diagnosis. at this point, he came upon the truly fearful thought that whatever was wrong with him, if there was, was not something that could be diagnosed, that just as he had gone to all of his doctors without possibly being ill and led them to such and such conclusions, it was just possible that, if this was itself the illness, not the being ill as such, but the thinking one was ill when one was not, was precisely the kind of thing not even a doctor could succeed in recognising. this meant he was truly alone with his illness, and that even if this was part of the illness, to be alone, it was not something he could then mention to anyone for it was, after all, part of the illness that it should either be impossible to explain or explore, leading anyone sensible who would have heard him speak on it think that his real illness was in thinking that he had an illness which no one could actually diagnose because it was nothing but the illness of thinking you were ill. this would force him to diverge sharply from the world, concluding as he might that while some thought he was ill in thinking he was ill when he was not ill, he thought he was ill in thinking he was ill when he was not ill in a different way, for while they believed in the possibility of someone intervening into his case to point this out to him, he saw the more problematic fact of his illness being so involved in the illness itself of its being something which one merely thought of as ill when one was not ill that there was no longer any intervention possible. it was the very presumption of intervention, after all, which would, if anything, constitute itself another illness, namely the belief that one was not ill when one was ill, whereas his was that he knew he was ill, but that his illness was such he would think he was ill even while he was not. he would be alone precisely because he could point this out and would make people think he was the person who was ill who was not really ill, whereas he was the person who was not really ill who thought he was ill who was not really ill. if they did not choose to look into his heart at that point and see the difference between his being not ill in thinking he was ill when he was not ill, which meant that he was that ill person who was not really ill, but was ill in thinking they were ill, versus his thinking he was ill when he was not ill, which was such a person who might have either contented themselves with the lie or was delusional. but, they would have to have believed something was truly out of his control for them to think that he could twice over believe he was not ill and still think himself ill, and if they refused this, was it not because they feared to let a man exist who was truly not in control? who in the depths of his construction who could not have even been imagined as being so? with each additional illness, did he become more aware or less? was this great illness not really just the ache then of how far he might go in imagining he oversaw himself, and that ever further back lay the illness itself? those who suspended their reason did so because at some point they had to imagine he was himself, that he was not ill at some point—but that was the paradox; he was ill in the very thought that he was not, and one could not presume that this was the control when it was the very absence of all certainty as to who he was which finalised his illness beyond himself. it did not invite him with it, nor did he superseed it; he simply remained in his radical activity, utterly aware of his illness irreducibly, utterly ill in the fashion of that consciousness, which no illness anyone could name could ultimately contend with or explain. he wondered then which appointmemt could he have had for this, or had he already scheduled one? was there, indeed, an appointment just for this, and it was his illness, this inescapable illness, which had in fact succeeded in finally having itself observed and this was to be the appointment which would rectify all past despair? if this was the appointment, he reasoned, then all past appointments, the mirage or hallucination of them, of course were part of that last distraction which was to make this one appointment ultimately stand out among them. unless, this was the one appointment then he had forgotten, and the remaining vestiges of this illness had succeeded in making him forget it—or had it not yet happened? was it about to happen? but, then this was it, he reasoned. there could be no date or time for this appointment, because, of course, all appointments had already succeeded in blindly pointing to it, right up until the point of utter uselessness and now that he was staring at the trees and the rain and this was the appointment, wasn’t it, he thought, this was the appointment in which everything about this illness would be observed and there would be an end to all despair, he thought, because this appointment had to be happening now or not at all, and if not at all then it was because the appointment hadn’t yet happened, and if it had happened and he had missed it and it was the appointment he had missed while it was raining and not raining then he just had to find the doctor and call him up and find out which was the appointment he had missed which all the others had been pointing to and the appointment where his illness would finally be observed and an end to all past despair, he thought, and if the appointment had not yet happened then it was probably happening right now, because it was raining and not raining, and if that was a hallucination then it was either meant to be raining or not raining, and it was raining and not raining and so the appointment was happening now probably because if it had not yet happened already then it was the appointment he had been waiting for and had probably missed, but then he just had to call the doctor and find out which appointment it was he had missed and to which all his other appointments had been pointing to and the trees were swaying outside and were still and it was raining and not raining and then his illness would finally be observed and there would be an end to all despair.